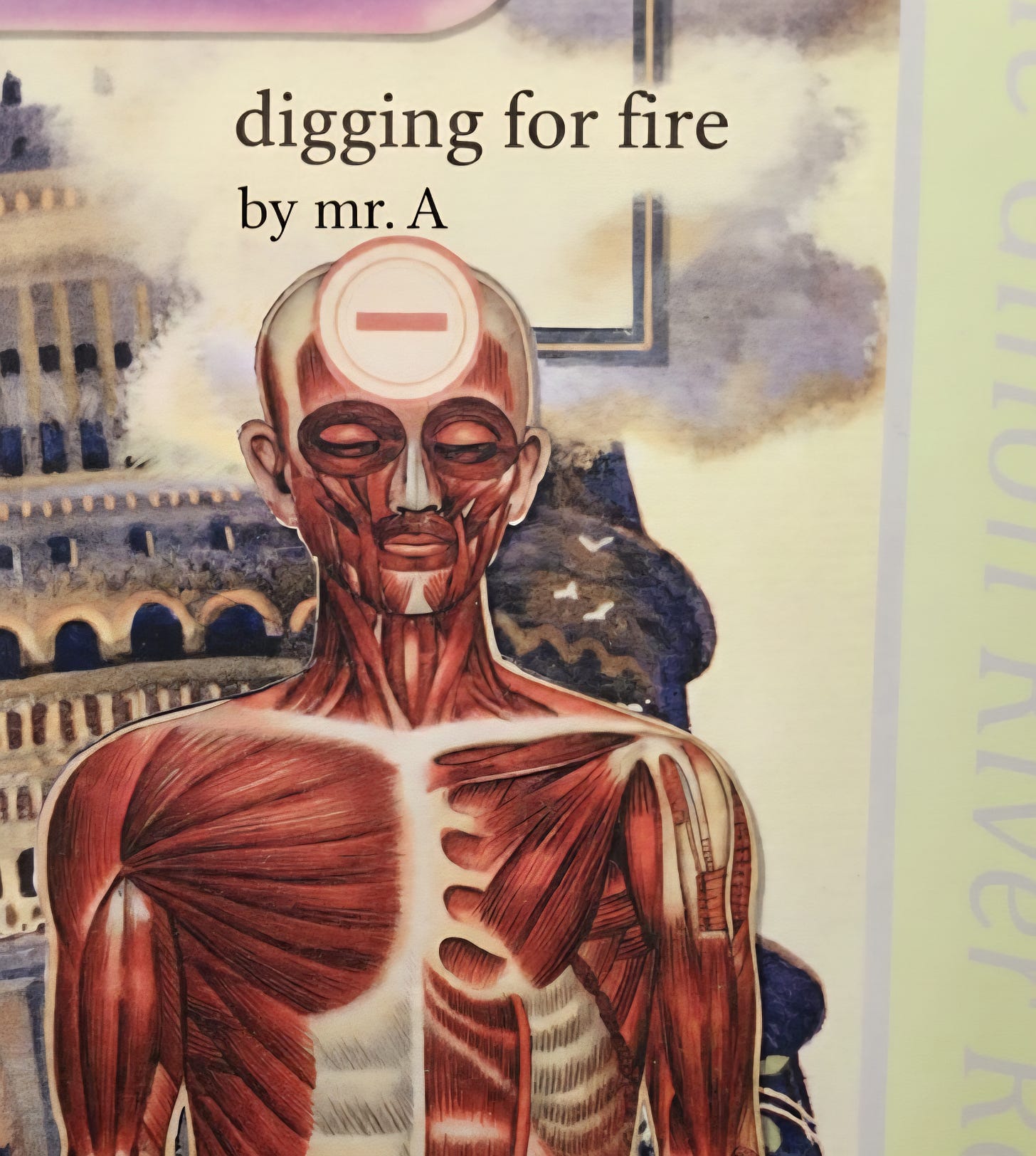

Digging for Fire

Myrna was prepared to meet the man from the other reservation. She told me that he lived far south of our reservation, and that his car was unreliable and it was likely that he would be late, but she assured me that he would visit us before the end of the day.

"We will see him before he sees us," Myrna said. From our small house on the hill we could see the horizon seven miles out to the edge, an empty plain of long yellow grass blown flat from the constant wind with one dark cluster of trees in the middle of it all. On occasion the wind would stop and it didn't feel right. Dead air was too quiet and you felt off balance until the wind picked up again. From the top of the hill we could see a car seven miles away, a black spot hauling a rising cloud of dust over the unseen dirt road.

Myrna said we needed to prepare two fires for the man to perform the blessing. I knew exactly what the blessing was, but I asked her what was special about this blessing, and she warned me to lower my voice. When she touched a finger to her mouth I didn't ask again. At my age I had to listen to her. I had just learned how to tie my shoes, black canvas low tops that I was proud to own ever since I knew how the laces worked. I always looked down at my feet to admire my tied shoes.

Myrna pointed across the yard toward two large holes with a high pointed hill of cold black soil next to each. "Gather enough twigs to fill each hole," she said. "The fire has to be high and hot when he arrives."

I stood between the holes and looked down. Each hole was deep enough and wide enough to cover my body, standing up to my neck. Until last week I was not old enough to tie my own shoes, but I was old enough to understand that if I fell into either hole I would be too short to pull myself out. The holes looked like ready graves for dogs or small people.

Where the sun-scorched pale lawn met the soft black soil around the tree was a stack of twigs. It was a head taller than me. The tree shaded most of the yard and killed the lawn. Farther back was the wooded area where we gathered the twigs on dry days in the fall. Last fall, I stumbled over a dead crow and never told Myrna about it. She always said a dead crow was a sign of bad air and if we breathed the same air as the crow we could get sick. While I held my breath I scraped a small hole with a pointed rock. With two twigs I rolled the solid crow into the hole, kicked the dirt over, laid the two twigs on top, and I knew the air was clean enough to breathe again.

I stood in front of the tall stack of twigs and branches and didn't know where to begin. Somewhere in the middle I pulled on a thick branch and the whole tower swayed with tight resistance as if each branch were joined by skin to the next.

"Turn around and look at me."

I turned around and Myrna was standing with her arms extended to show me what to do with my arms.

"Hold your arms out in front of you like this," Myrna said. "And close your eyes."

I felt the scratch of twigs and branches poke through the sleeves of my shirt until the last branch brushed under my chin.

"You can open your eyes now," she said. "You see, they're not heavy, they're just poky and hard to gather up. Now go ahead and drop those into the first hole. Be aware of where you're stepping and watch your eyes when you look down. You don't want your eyes getting poked out."

At the first hole I turned my head to the right before I looked down. At the bottom Myrna had placed a layer of fourteen round stones big as cantaloupes, dark grey stones speckled with white that shone through the circle of thick cut logs piled two-high around the interior perimeter of the hole. I let go the twigs and branches and they crackled and stopped all at once and covered the stones. After six more trips, three trips to each hole, I lost interest in the work and wanted the fire to start. I wanted to light the rolled up newspaper and drop it in, stand back, and watch the fire wave grow up and over the edge. But Myrna started the fire and said I could light the ceremony when I turned ten years old and earned my first fire ditch.

"You will have to dig it yourself. I started digging when I was nine and a half," Myrna said. "For six months I dug a little each week, then I lit my own, my first ten year old fire ditch."

We both stood back as the fire grew and sent dark smoke across the mid day sun that provided hot shade over our faces. Myrna kept adding more branches to keep up the flames.

Then she stopped to watch the road. Her posture was straight and alert.

"He should be here soon," she said.

I stood behind her and studied her long black braided hair. The unbraided strands at the bottom just touched her beltline, and as she traced the horizon her braid inched across her back. Out near the lower edge of the sky was a fast cloud of dust, a tractor-trailer that dropped out of sight as fast as it appeared.

Then Myrna talked to me. "Today I'm twenty years old, and he should be here. It's a special time when you earn your second fire ditch. He has earned his fourth so maybe he forgets what it meant to him twenty years ago on his second." Myrna's eyes raced in her head because she did not blink when she spoke. At the end of her sentences she would blink once to signal a period, an indication of your turn to speak or acknowledge what she had said. I didn't speak, but she knew I had listened by the way I looked at her, caught in her pale brown eyes. The whites of her eyes were pink and strained and the pupils tall and stoic. That's what I thought at the time. I learned one thought at a time from her cutting eyes that did not blink, always set and ready to say more. When she bent down in front of me I watched her button-up blouse. It drooped and hung suspended like a hammock. I looked down at the two shapes under the solid navy blue blouse that rivaled her olive cream skin.

"Hey, don't look down there," she said. She held her hand flat on her chest. "You're too old to be concerned with that part of me now." She sat on the ground, crossed her legs, and leaned back on both hands. "Sit next to me," she said. Her eyes were quiet and her voice was soft now. "I sat next to her. "I'm not a girl anymore. I've been a woman six years now, and thanks to me, you're old enough to tie your own shoes, and in four years you will light your own fire, and I will help you the same way you helped me today. God knows I helped him with his fourth ditch. You'd think he'd keep his word and assist me on my second. I contacted him dig his ditch because of his weak back. That night at the bottom of the ditch we fell in love more than once. I know for certain that's where you were started. I knew it. I felt the early science of you in my belly."

With both hands, Myrna held an invisible ball over her stomach. Then she nudged me with her elbow.

"Are you listening? I know you understand."

I remembered girls at the grocery store with round bellies and Myrna told me it was rude to point.

"That's where you were before you were born. And everyone pointed at my belly and whispered. They knew he wasn't right for me. Right or not, he was nice back then, nice enough to hide a bouquet of white daisies at the bottom of the ditch for me to have. He told me that I would only have flowers just this one time, and when they died I would have to remember how they looked and felt in my hand, fresh and alive. He said that he loved me too, but no one else would understand how he could love me that way. He said that I shouldn't tell anyone, that I was too young to be getting flowers from a man his age. After he boosted me out of the ditch it was the middle of the night, and the low moon was full. It whitewashed the soil on the palms of my hands and the ground-in soil on my bare knees. My hands and knees were sore, but it felt good to be sore like that. I left my flowers at the bottom of the ditch and I wanted to go back down there so I could have them for a keepsake, but he said it was too late for that. He had to go and he wanted me to leave too. He covered me under his arm and walked me fast to his car, and we sped off and didn't stop until he left me a mile from home. He forced me out of the car and said he still loved me and that he would surprise me with a letter or call me or stop by when he saw to it. But if he didn't see me for a while it would make it that much better when we did see each other again."

The fire had died down and thin white smoke drifted from the hole and the wrinkled heat bent the sky behind it. Myrna sat on the ground between the two holes with her legs crossed, and covered her face with her hands. Then she removed her hands and watched the smoke leave the holes until it blended into the sky. I asked her what to do.

"Nothing," she said. "Just stay here next to me." She leaned back on her elbows, lowered her head, and smiled at me. I didn't like it when she smiled; a smile meant I had been wrong. Two weeks earlier, I had broken her flyswatter and I hid it under the sofa. She had asked me where it was, and I swore to her I hadn't seen it or used it in a long time. Then she found it, both halves of the plastic flyswatter, and she smiled at me.

"Don't grow up to be a liar," she said.

I didn't know how to answer her. If I had said I wasn't a liar she would have known that was not true. If I said I would never lie again I wouldn't have believed it. I hid the broken flyswatter from her. I didn't tell her about the dead crow. I didn't tell her a lot of things. I always wondered if forgetting was a safe way to lie. I forgot to tell her that he called two days before the blessing and I had picked up the phone on the first ring while she was outside digging the second ditch. It was right before dinner. She had made my favorite meal; fried chicken wings, mashed potatoes with pan giblet gravy, and green beans with toasted slivers of almonds. He said to give Myrna an important message. To tell her he couldn't make the blessing because he was in jail again and he had to get off the phone right away. He said he saw a picture of me in a white shirt and that I looked handsome in white, and that I was a good boy to help Myrna.

Think Mr. A

This is quite the piece, Mr. A. Wonderful stuff. Read it twice.

I read it three times (read twice, listened once). I'm still lost for words. I have too many thoughts, among them the wish to ask you if you yourself are aware how good this is, and also the thought that I have a real author nearby on that platform who posts jokes and himself in a Teletubby costume. I'm too impressed, I can't form my thoughts coherently. This was unbelievably good.